This resource answers common questions about immunoglobulin replacement therapy at our Trust. If you would like further information, or have any worries, please do not hesitate to ask your nurse or doctor.

In all cases, a doctor will explain immunoglobulin replacement therapy to you and answer any questions you may have.

We understand that coming to hospital can be a worrying time and you probably have some questions about your condition that you hadn’t thought of when you were last with us.

The immune system

The immune system is the body’s natural defence mechanism, consisting of various cells, tissues and organs and is our way of protecting ourselves from harmful organisms such as bacteria, fungi and viruses.

These are also known as antigens or pathogens. When your body encounters them, it will try to defend itself and the immune system is how it goes about it.

White blood cells (also known as leukocytes) make up a very important part of the immune system and have two main types:

- Phagocytes: These are cells that swallow up and digest any bugs or cells which have been identified as harmful. The most common type is the neutrophil.

- Lymphocytes: There are two types of lymphocytes, which are B and T cells. Both are responsible for recognising and remembering antigens which you have come into contact with before. They are more specialised in how they work and help you to become immune to certain diseases.

Immunoglobulins

Immunoglobulins are a type of protein and an important part of the immune system. They are made by B-cells and are also known as antibodies. There are three main types:

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies are the first to react to the threat of antigens and are important for the first few days of infection.

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies are found in the mucosal areas of the body and protect those areas with a high antigen concentration and where the physical barrier (mucous membrane) is less effective than the skin. The nose, mouth, digestive tract, and eyes are all areas where IgA can be found.

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies are perhaps the most important of the antibodies and are found throughout the body. They are produced in far higher quantities and can recognise and attack particular antigens. Particular IgG antibodies will match up with the antigens and help destroy them. They can also signal other immune cells to come and help.

Immunodeficiency

People with immunodeficiencies are less able to fight infections as their immune system is not working properly, either partially or not at all. They generally get infections more frequently and will also tend to take longer to recover from them.

The infections normally appear around the lungs (chest infections), the nasal passages (sinusitis) or the gut (diarrhoea). In the UK, roughly 5,000 people are thought to be affected, although this figure is steadily rising with a greater understanding of the condition.

If you have been diagnosed with an immunodeficiency you do not need to panic. Most conditions that fall under the term can be managed very successfully with medical treatment. Some patients may only need to have regular check-ups or clinic visits to have their blood tested.

Others will need to take regular antibiotics to limit the number of infections they have been having. A few will need to have essential antibodies replaced by intravenous (IV, which means into a vein) or subcutaneous (SC, under the skin) infusions. This helps to boost the immune system to a level comparable with unaffected people.

Some children with a severely compromised immune system can have it replaced with a healthy one by bone marrow transplantation. This is a well-understood and mostly successful procedure, however, its use in adults is limited. New treatments, such as gene therapy, are also being developed for some more severe forms of immunodeficiency.

Primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs) are immunodeficiencies that people are born with or develop spontaneously later in life without any obvious reason. There are many different types of primary immunodeficiencies with varying degrees of severity.

The causes are thought to be mostly genetic and will depend on the gene or genes affected and the amount of mutation present. About 20 per cent of patients found to have a primary immunodeficiency will also have a close family member affected, although not necessarily with the same condition.

There is a lot of research currently trying to discover more about the causes of immunodeficiencies, some of it carried out here at the Royal Free Hospital.

Secondary immunodeficiencies (SIDs) are those that are acquired later in life and can be due to infections, some types of cancer or from certain drug therapies such as chemotherapy, immunosuppression, antimalarial treatment or epileptic medication.

Important information about HIV: A lot of people when they hear the term immunodeficiency automatically think of HIV or AIDS. This is a completely different condition, caused by a virus, and is not the same. Primary and secondary immunodeficiencies are not related to HIV or AIDS.

Treatment

There is much that is still not understood about problems with the immune system and consequently, new treatments and research is being carried out all the time to improve the quality of life for people with immunodeficiencies.

The UCL Institute of Immunity and Transplantation (IIT) at the Royal Free has an important focus on research into primary immunodeficiency disorders to improve diagnosis and care.

The treatment for primary and secondary immunodeficiency is the same and usually involves infusions of antibodies to replace those not already present.

This is typically given into the subcutaneous layer of tissue (the deepest layer of your skin) around the abdomen or upper thigh – called subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy (SCIg) - and carried out at home after appropriate training.

Many patients find home therapy a convenient way to have treatment with minimal disruption to their day-to-day lives with research also showing an increase in their quality of life.

Alternatively, the treatment can be given intravenously, or straight into a vein – called intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg) - which would take place at the Royal Free on our day ward, at a local hospital closer to your home or at home after training.

There are a number of different manufacturers making immunoglobulin replacement therapy and you may hear us refer to them as ‘products’. Naturally occurring antibodies (specifically IgG) found in human blood plasma are the essential components of all these products.

This is obtained from screened donors and purified using a lengthy and complex filtering system to ensure that, as much as possible, any harmful components are removed. The main way these products differ is in the solution they are dissolved in and the concentration. For most patients, one product will be as good as another.

Why do I need the treatment?

The term immunodeficiency means that your immune system is not working fully and therefore needs help to fight off infections caused by viruses and/or bacteria and/or fungi (pathogens).

Usually your body produces immunoglobulin (antibodies) all the time to help keep you well but often an immunodeficient person is not able to do this and can become easily unwell. The antibodies that should be present in blood need to be replaced through infusions and this is where the term ‘replacement therapy’ comes from.

As already mentioned, these replacement products are sourced from many donors, which means they contain a wide range of antibodies effective against most of the general pathogens within the population.

This does not mean, however, that you will now be protected against all kinds of pathogens. At best, being on replacement therapy will mean that you have a similar chance of catching common infections as anyone else.

It is vitally important you look after yourself by maintaining good hygiene, taking regular exercise (especially if you already have lung damage), eating a healthy diet and, most importantly, not smoking.

Having your treatment

Before starting any treatment, a doctor and one of the nurses will explain to you what this involves, giving you a chance to ask any questions you may have. If you are still unclear about anything, please use the details given at the back of the booklet to contact us.

We are always happy to discuss issues relating to your treatment and understand that this may be a confusing time for you and your family.

Treatment options

The amount of immunoglobulin you need is worked out by your body weight initially. There are two ways of having an immunoglobulin infusion:

- IV (intravenous – into your vein)

- SC (subcutaneous – into your skin).

Both routes involve having the same amount of immunoglobulin over the course of a month. Each method is acceptable and has certain advantages over the other.

The one you decide upon will depend on your personal preference and we would support you whichever you choose. It is also possible to change from one to the other at any time.

For most patients having Conventional subcutaneous (SC) infusions is the preferred option as it tends to bring about fewer side effects, is very easy to learn and has the convenience of being very flexible.

It involves a small needle being inserted into the fatty layer of tissue under the skin around the abdomen or upper thighs, rather than into a vein. This means it takes longer for your body to absorb the liquid and acts like a slow-release mechanism.

It is one of the reasons why SC treatment is generally tolerated better than IV and because smaller doses are given at one time. However, it does mean that they need to be given more frequently.

Possible side effects around the needle site are common such as swelling, itchiness and redness although this only lasts for a short while and is not generally a problem. SC is easier to learn and, although carried out weekly or more often, infusion times are much less, compared with IV.

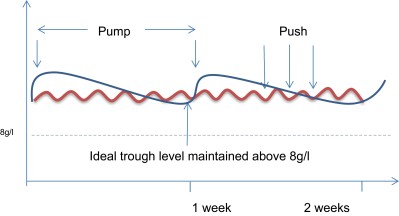

It will also give you a more even level of immunoglobulin throughout the month (see diagrams on pages 13 and 14). There are two methods for SC treatment: manual push and weekly pump.

This is the easiest method to learn and the quickest to carry out but needs to be done more frequently. It involves 2g (10-12.5ml) injections of immunoglobulin, given by hand, and which usually take no more than five to 10 minutes, depending on your preference.

The number of times per week will depend on your overall dose, the average being around 8g (4x2g injections per week). There is a lot of flexibility with when it can be given. It normally takes two to three training sessions to learn how to do this yourself.

This involves the weekly immunoglobulin dose usually being given on a single day via a pump and into a single or, more often, multiple sites. This will usually take between 30-60 minutes to complete depending on your preference.

This is a simple procedure, but because there are more steps involved, learning how to do it yourself usually takes between three to six training sessions.

fSCIg is a combination of the conventional subcutaneous method and IV dosing. The addition of an injected enzyme (hyaluronidase) into the subcutaneous fatty tissue allows far greater volumes to be infused in one go, meaning it needs only to be given every three to four weeks, like an IV dose.

However, it is generally tolerated better than IV infusions. For more information on this method follow the HyQvia link in the useful websites section towards the end of the page.

Intravenous infusions go directly into a vein in your arm or hand using a small butterfly needle. We try to rotate the veins used so they can be rested and kept working for as long as possible.

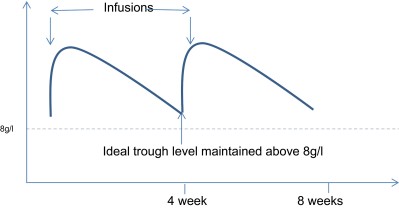

Once established on a suitable IV product, your treatment will typically take place every three to six weeks and should take about two to four hours. Having your infusion IV means that a higher dose can be given at once, which is why you do not need to infuse so frequently.

The downside to having IV treatment is that you need to have veins which can be accessed easily, and the side effects can be more noticeable due to the higher dose given in a single infusion.

IV infusions can also be carried out at home although you would need to start your IV treatment in hospital first to ensure you are able to tolerate it well.

Simplified diagram of IgG levels using SCIg “pump” and “push” method

Simplified diagram of IgG levels for IVIg infusions

Risks and side-effects

There is a possibility that you may have a reaction to the product you are on, although this is not common. This could mean feeling faint or dizzy, experiencing lower back pain, shortness of breath, itchiness, or a headache.

Often, this will only happen the first few times you have an infusion but occasionally it can continue. If so, we may consider changing your immunoglobulin product. This is nothing to worry about. It only means that your body is a little sensitive to that solution and not to the essential ingredient (immunoglobulin) within it.

Infusion reactions can also occur if you have an active infection. Sometimes we need to delay your infusion until your infection has been treated. Please let us know if you are unwell when you are due to have your infusion, so we can discuss whether to delay your infusion or not.

Blood testing

Having your blood taken is necessary for us to monitor how your treatment is going. If you start on replacement therapy, we will need to monitor the levels of immunoglobulin in your bloodstream approximately every six months.

This allows us to find out if you’re getting the right dose, as your needs may vary depending on the number and severity of infection you’re experiencing.

We may, from time to time, ask you to give some blood to help in our research projects, but this will only be a small amount and only when you’re already having blood taken. There is no obligation to give blood for research and we will always ask for written consent before doing so.

Psychological treatment

Whilst many people with immunodeficiencies are managing their condition and the impact it has on their lives well, we know that this is not true for everybody.

There is a link between physical health and mental well-being, and adults with chronic illnesses are at increased risk of suffering from anxiety and/or depression than the general population.

Poor mental health can also affect your ability to manage your physical health. Within the department, we have a psychology service that can provide short-term, talking therapy to patients with immunodeficiencies, or support patients to find other more suitable services locally.

The treatment aims for those using the service vary and can include improvements in mood, general anxiety, specific anxiety about health issues, sleep and fatigue (tiredness). It is also a space to reflect on the impact the illness has on your own and others’ lives.

We use a practical, cognitive behavioural model of treatment which helps you try out different techniques and skills which can make life easier. If you would like to find out more about the service or discuss the possibility of an assessment appointment, please ask one of the team.

Jeffrey Modell Foundation

Since 2009, the Royal Free Hospital has been a Jeffrey Modell Foundation (JMF) centre. We are dedicated to early diagnosis, meaningful treatments and, ultimately, cures through research, physician education, public awareness, advocacy, patient support and new-born screening.

Vicki and Fred Modell established the JMF in 1987 in memory of their son Jeffrey, who died at the age of 15 from complications of primary immunodeficiency.

Antibody: a protein made by B cells which can destroy antigens. Also known as immunoglobulin.

Antigen: general term for something that is recognised by your immune system as harmful and triggers a response. Common antigens can include particles from bacteria, viruses and fungi.

B cell: a protein and type of lymphocyte. Source of antibodies (immunoglobulin) which locks on to specific antigens, triggering their destruction with the help of other immune cells.

Bone marrow: the inner part of the bone where immune cells and antibodies are produced.

Intravenous (IV): literally means into a vein and is the alternative route for replacement therapy.

Immunoglobulins: proteins made by B cells and also known as antibodies. There are three main types: IgM, IgG and IgA.

Lymphocyte: a type of white blood cell mostly produced in bone marrow. Also known as T or B cells. Both are responsible for recognising, remembering, and helping to kill pathogens.

Lymph nodes: Site of antigen and lymphocyte interaction and one of the sites for antibody production.

Lymph vascular system: carries antibodies and antigens throughout the body.

Neutrophil: the most common type of phagocyte or ‘cell eater’. Pathogens: any kind of harmful agent, typically bacteria, viruses or fungi.

Phagocyte: a group of white blood cells which engulf and digest harmful cells.

Replacement therapy: the term used to describe immunoglobulin infusions.

Subcutaneous (SC): refers to the fatty layer of tissue just under the skin and is the preferred route for replacement therapy.

Spleen: site of B cell maturation and where blood cells, platelets and antigens are broken down. This can become enlarged in some patients.

T cell: a protein and type of lymphocyte. Like antibodies, they react to specific antigens. Comes in three types:

- Killer T cells (CD8+): destroy cells invaded by bacteria or viruses but also cancerous cells and foreign tissue such as transplanted organs.

- Helper T cells (CD4+): activate killer T cells and stimulate B cells to make antibodies.

- Suppressor T cells: moderate the immune response and prevents the immune system from going into overdrive which could lead to an ‘autoimmune’ response where the body’s own healthy cells are attacked.

Thymus: small organ located behind the sternum (breastbone) and site of T cell maturation.

Trough level: the term used to describe the lowest point of your infusion cycle (just before your next infusion) once on immunoglobulin replacement. This is the point we measure your level, so we know it is no lower, only higher.

White blood cells: (also known as leukocytes) are the main component of the immune system. The two main types are phagocytes and lymphocytes.

Immunodeficiency UK: an independent charity for patients with primary immunodeficiencies and their carers. It has many excellent pages with reliable information on a variety of topics, a lot of which will also be relevant for patients with secondary immunodeficiencies.

The Institute of Immunity and Transplantation: based at the Royal Free Hospital. You can find lots of information about the research currently being conducted in immune-related conditions.

The International Patient Organisation for Primary Immunodeficiencies: this website has a broad range of information covering patient issues, drug and treatment developments, legislation and much more.

The Jeffrey Modell Foundation: helpful information on primary immunodeficiencies and terms you may hear used in our clinics as well as other resources.

European Society for Immunodeficiencies: Exchange of ideas and information among doctors, nurses, biomedical investigators, patients, and their families concerned with primary immunodeficiency.

The UK Primary Immunodeficiency Network (UKPIN): a multidisciplinary organisation for those caring for patients with primary immunodeficiencies. UKPIN aims to share methods of best practice, and to accredit immunology centres which practice in this way.

Primary Immune: an American organisation for patients with immune deficiency. It has some excellent patient education resources and other up-to-date information.

HyQvia: for information on how HyQvia is different to conventional SC and IV immunoglobulin treatment. It is an American site so contains some information about payment or insurance which is not applicable in England.

This website is run by the pharmaceutical company that makes HyQvia, but this does not mean we prefer this product over any of the other immunoglobulin products available.

Translate

Translate