“My grandmother was the first to notice something wasn’t right,” recalls Zehra. “I was always tired and lethargic, and sleeping far more than other children. That led to a blood test, and I was diagnosed with thalassaemia.”

Thalassaemia is a genetic blood disorder that affects the body’s ability to produce haemoglobin. Without regular transfusions, people with severe forms of the condition can become dangerously anaemic.

“Now, I need blood every four weeks, and it takes the whole day,” she says. “Without it, I get weak very quickly or fall ill. My tolerance is lower now — and I need these regular blood transfusions to stay well, keep my energy up, and live a normal life.”

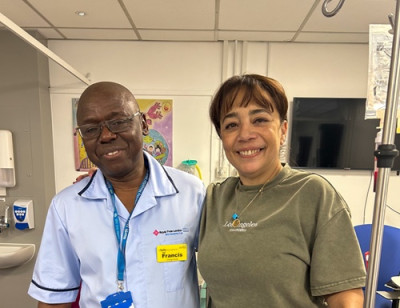

Zehra, a part-time Turkish interpreter, receives regular blood transfusions at the specialist haemoglobinopathy unit at North Middlesex University Hospital - one of the UK’s largest centres for diagnosing and treating red blood cell disorders such as sickle cell disease and thalassaemia. She describes the staff there as family, including specialist nurse Francis Mate-Kole (pictured), who has played a key role in her care.

She also draws strength from her two sons, aged 26 and 21 and close family. “My mother, father and brother were all tested when I was diagnosed, and they were found to be thalassaemia carriers. We’re keeping a close eye on the children in the family.”

Zehra is a trustee of the UK Thalassaemia Society (UKTS), a national charity which aims to improve the lives of all those living with the condition.

Now, Zehra is using National Blood Week to highlight just how critical donors are to people like her.

“Please, if you can, give blood,” she urges. “It’s not just a bag of blood — it’s hours, days, even years of life you’re giving to someone. For people with thalassaemia, it means everything.”

To find out more about blood donation or to register as a donor, visit NHS Blood and Transplant.

Translate

Translate