A digital platform which allows doctors to closely monitor liver disease patients while they are at home can lead to a reduction in hospital admissions, according to a new study.

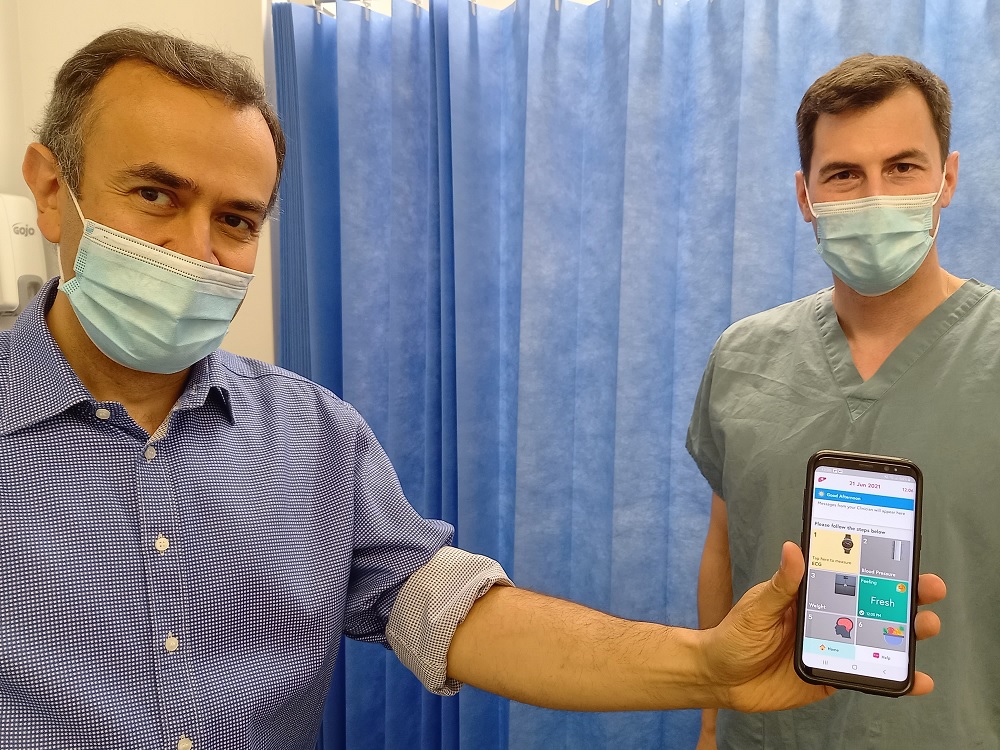

The CirrhoCare® App, was trialled for the first time at the Royal Free Hospital by liver consultant Professor Raj Mookerjee and his team. The study required patients to take a range of daily measurements including blood pressure, weight and their ECG using simple hardware technology.

Their information was blue-toothed to the app and relayed via a secure server and digital platform, to help liver specialists spot any potential deterioration of health in their patients. Then, if needed, they were able to intervene early with advice to adjust medications or fluid intake, to help cirrhosis patients avoid unnecessary hospital admissions.

Currently patients with end stage liver disease often experience a rapid decline in their health which can result in multi organ failure and invariably acute admission to hospital. They are often in and out of hospital and may require intensive care treatment, including support with ventilation and their kidneys.

But Professor Mookerjee found that patients using the technology were much less likely to need hospitalisation compared with those not using it – and if they needed admitting, patients using the app were likely to be discharged sooner and needed fewer outpatient procedures, such as abdominal fluid drains.

“The participants said it was easy to follow the instructions, gave them a focus and a better understanding of their condition and it helped them feel more in control,” said Professor Mookerjee.

“These are very sick patients for whom the average mortality may be as high as half within six to 12 months. For us, it was very helpful because we could tell if, for instance, someone was struggling with their brain dysfunction or fluid accumulation, and arrange for changes to their treatment in the community, or if needed, bring them into hospital to help them.”

As well as daily measurements, the app prompts patients to provide information about their well-being, plus food, fluid and alcohol intake via simple drop-down menus. In addition they are also asked to do a modified ‘Stroop test’ – a simple animal naming test - to measure their brain function. All the patient information is made available on a clinician display and evaluated by liver clinicians who are then able to get in touch via phone or text on the patient app as needed.

During the study period there were eight liver-related admissions for the group using the app compared with 13 in the observed control group. For the group of patients using the app, hospitalisations averaged five days, which was shorter than that seen in the control cohort, where some patients were admitted for greater than two weeks. In addition, the study team contacted a further 16 patients for additional guided interventions such as advice on fluid intake, diuretics and laxatives, which also reduced the need for further hospital assessment.

Professor Mookerjee, added: “Up until now, this group of patients has had to rely on reactive medicine when they became sick, which was particularly an issue during the bed-pressures of COVID-19. Now for the first time, we have the technology to monitor and manage cirrhosis remotely and proactively, and the information patients provide, gives us a daily insight into their health which means we can intervene earlier. This is very much personalised treatment, whilst empowering patients to be more involved in their care and be aware of changes to their condition.

“We had been wanting to see if we could do more in the community but COVID-19 hastened this because we were needing to reduce footfall in the hospital.”

He said: “Care provided to these patients will always be led by doctors but if we can predict complications early, then there’s no reason why we can’t pre-empt interventions required and set thresholds for treatment, which means in the future, we would be able to send ‘push’ notifications to some patients to change their treatment whilst at home. For example, if they start accumulating a lot of water in their belly, the app could alert them to reduce their fluid intake and/or increase their diuretics. Early digital interventions like these could make a huge difference to patients’ quality of life and potentially reduce the pressure on the NHS.”

Now the small study of 20 patients has shown promising results. Professor Mookerjee is hoping to conduct a larger study and says improvements like this for treatment of cirrhosis patients can’t come soon enough.

He said: “As a consequence of the pandemic we are seeing more patients. People were certainly drinking more alcohol and the isolation they experienced exacerbated their intake. Approximately 70% per cent of cases of liver disease we see in our unit are alcohol related. If we can harness technology to find a better way to deliver care, then we should do it.”

The study was funded by INNOVATE UK, and granted a further extension fund. Applications for grants from other NHS and public large scale funding streams are being sought to facilitate a larger controlled trial and further development of the system.

Results from the abstract of the study were announced at the International Liver Congress last week and the full study has been submitted for publication.

Pictured L-R: Liver specialist Professor Mookerjee and senior clinical research fellow Dr Konstantin Kazankov with the CirrhoCare® App.

Translate

Translate