Tiny beads of carbon which can barely be seen by the naked eye could transform the way we treat a range of diseases and save thousands of lives, according to researchers at UCL and the Royal Free Hospital.

The minute beads – which come in a small sachet – are designed to remove harmful bacteria from the gut and reduce inflammation inside the body.

It is hoped the beads, known as CARBALIVE, will ultimately help patients with a range of inflammatory conditions, including liver disease, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and more.

Research published today has found the beads, which are taken orally and excreted unchanged, to be safe for patients with cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) – and following this a further study needs to take place to look at whether they are effective in treating the disease.

Patients with cirrhosis suffer from inflammation due to migration of harmful bacteria and its products from the gut to the blood, which in turn allows growth of more harmful bacteria. This leads to weakening of the immune system, making them susceptible to bacterial infections. Sepsis (an infection of the blood) is the main reason for intensive care unit admission and death for patients with cirrhosis.

The research team, led by Professor Rajiv Jalan, hope the micro beads will change the composition of the gut, making it impossible for harmful bacteria to survive, while allowing good bacteria to thrive. This in turn could mean fewer cirrhosis patients needing hospital care and may help slow or even reverse progression of the disease.

Professor Jalan, from the UCL Institute for Liver and Digestive Health and a consultant hepatologist at the Royal Free Hospital, said: “The study in animals with cirrhosis has shown us that these beads prevent progression of liver scarring, progression of cirrhosis and liver failure. Studies in patients has confirmed that the treatment is safe and well tolerated. Now we need to do a larger study in patients with liver disease to assess its impact on the progression of the disease.

“The hope is that in the future this could also prove an effective treatment for other diseases associated with a change in the composition of the gut bacteria such as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and even potentially for Parkinson’s Disease.”

The beads are designed to be taken once a day with water before bed. They are inert and pass through the body ending up as waste.

As harmful bacteria is more likely to move at night from the gut to other parts of the body where they can cause damage, it is hoped that taking the beads before bed will stop them in their tracks.

Unlike antibiotics, the beads don’t kill the bacteria, which means there is no risk of increasing antibiotic resistance.

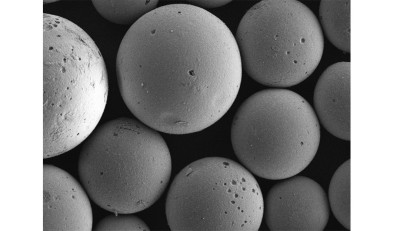

Professor Jalan added: “Although the beads are only 250 microns in size, so small as to be barely visible to the naked eye, they also contain lots of holes and the typical dose of 4 grams has 6,000 square metres of surface area – nearly the size of a football pitch. This means they are incredibly effective in the gut which contains trillions of bacteria and has a huge surface area.

“This all began as a PhD project in 2011 by Dr Jane McNaughton, a UCL hepatologist, and now we have a safe, relatively cheap product which could potentially, if found to be effective, impact on many diseases which are associated with changes in the gut microbiome.”

Crucially because CARBALIVE is not deemed a medication as it is inert and excreted unchanged, if found to be effective in a further trial and brought to market it can be labelled as a device, which could see it available to treat patients in the next two to three years. It is being further developed by a company, Yaqrit Ltd. (www.yaqrit.com), that was spun out of University College London and has licensed the technology.

The early phase trial – Clinical, Experimental and Pathophysiological effects of Yaq-001, a Non-absorbable, Gut-restricted Adsorbent in Models and Patients with Cirrhosis – has been published in Gut, a leading international journal in gastroenterology and hepatology. The project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

Currently 110 million people in the world suffer from cirrhosis and the typical life expectancy of a person with liver cirrhosis is around two to 12 years.

CARBALIVE beads viewed with a scanning electron microscope

Translate

Translate